The Newsletter | No.68 | Summer 2014

‘Silence is the best solution’ Louis Zweers

Unconscious dominions Julia Read

Bodies in Balance – The Art of Tibetan Medicine Theresia Hofer

The Study page 8-9

The Review page 32-33

The Portrait page 48

theNewsletter

Encouraging knowledge and enhancing the study of Asia

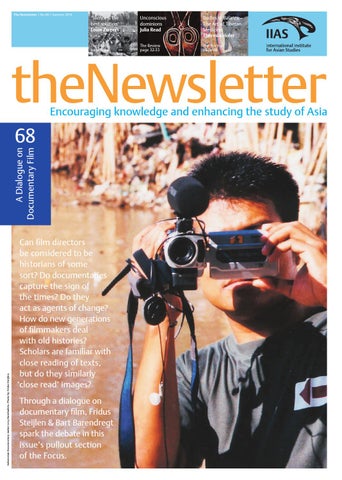

Indonesian Documentary maker Lexy Rambadeta. Photo by Fridus Steijlen.

A Dialogue on Documentary Film

68

Can film directors be considered to be historians of some sort? Do documentaries capture the sign of the times? Do they act as agents of change? How do new generations of filmmakers deal with old histories? Scholars are familiar with close reading of texts, but do they similarly ‘close read’ images? Through a dialogue on documentary film, Fridus Steijlen & Bart Barendregt spark the debate in this issue’s pullout section of the Focus.

2 | The Newsletter | No.68 | Summer 2014

Contents

3 From the Director

THE STUDY

4-5 Bali at war: a painted story of resistance to colonial rule Siobhan Campbell 6 Learning from Hong Kong: ‘place’ as relation Renske Maria van Dam 7 ‘Home and Away’: female transnational professionals in Hong Kong Maggy Lee 8-9 ‘Silence is the best solution’: The military versus the media in the Netherlands East Indies 1945-1949 Louis Zweers 10 The challenges to female representation in Asian democracies Timothy S. Rich and Elizabeth Gribbins 11 Like wildfire Special feature page: The Writer Ronald Bos 12-13 Images of Vietnam in the art of katazome, by TOBA Mika Special feature page: The Artist Stefan Jeka 14 Satyamev Jayate: a quiet Indian revolution Special feature page: The Opinion Rituparna Roy THE REVIEW

15 New for review

16 Uncivil society Nicholas Tarling 16-17 Geopolitics of energy Henk Houweling 17 Engaging the spirit world Niels Mulder

18 New reviews on newbooks.asia

THE FOCUS

19-30 A Dialogue on Documentary Film Fridus Steijlen and Bart Barendregt Guest Editors

THE REVIEW continued

31 Matches and gunpowder: the political situation in the East China Sea Matthijs de Boer 32-33 Unconscious dominions Julia Read 33 Encountering a new economic powerhouse Emilian Kavalski 34 Encounters with Europe Barnita Bagchi THE NETWORK

35-37 Reports 38-39 News from Southeast Asia 40-41 Outreach

42 ICAS

43-44 Announcements

45 IIAS Research and Projects

46-47 IIAS Fellowship Programme THE PORTRAIT

48 Bodies in Balance – The Art of Tibetan Medicine Theresia Hofer

The Focus A Dialogue on Documentary Film 19-21 During the International Documentary Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) last year, a seminar was held in the context of the theme program ‘Emerging Voices from Southeast Asia’, in which some of the filmmakers involved shared thoughts about each other’s methodologies and ongoing concerns with scholars studying Southeast Asian contemporary culture. Guest editors Fridus Steijlen and Bart Barendregt present a number of articles in this issue’s Focus section as a response and extension to the discussion. 22

27

Raul Niño Zambrano, the curator of the IDFA ‘Emerging Voices’ program reflects on his tour through Southeast Asia and his search for films to be included in the festival.

The essay by Nuril Huda shows how in Indonesia a novel genre of pesantren film is emerging from Islamic boarding schools, now that new regulations have enabled the insertion of more ‘secular’ subjects into the schools’ curriculum.

23 Gea Wijers’ contribution illustrates how a young generation of Cambodian filmmakers comes with its own preferences in writing history, focusing on the pre-and post-conflict periods, rather than the pain and trauma that accompanies the Khmer Rouge conflict for so many.

24-25 The best way for us to represent the often complex entities we are studying is to listen to the manifold voices trying to speak to us, which is what Farish Noor is trying to do in a new documentary series on Indonesian culture and politics he is currently directing.

26 Documentary filmmakers’ depiction of national history seems much dependent on personal experiences; see, for example, the divergent ways Rithy Panh and Joshua Oppenheimer chose to depict mass violence and genocide, both described in John Kleinen’s essay.

28-29 Keng We Koh acknowledges the relevance of film in addressing and redressing historical themes. However, as with teaching all history, an appropriate context is a top requirement if one is to understand such remakings of the past.

30 Erik de Maaker shows how changing conditions such as the rise of commercial TV and the resultant breakdown of government control has provided Indian filmmakers with opportunities to gain control of their own agenda.

The Newsletter | No.68 | Summer 2014

From the Director | 3

Studying Asian heritages

Epsos.de/flickr

After the celebrations of IIAS’ twenty year anniversary, I can now return to a more regular recounting of what the institute is up to and how the different programmes under the three thematic clusters are progressing (Asian Heritages, Asian Cities and Global Asia). Philippe Peycam

The second major breakthrough in the field of heritage studies is the establishment of a trans-regional graduate programme on Critical Heritage Studies in Asia and Europe. IIAS is here acting as a ‘middleman’ between universities such as Leiden, National Taiwan, Gaja Madah and Yonsei. Under the coordination (and teaching) of Dr Adele Esposito, the MA programme track started officially in September 2013 in Leiden. Its Taiwanese counterpart will begin in Taipei next September, under the coordination (and teaching) of Professor Hoang Liling. We expect to see our Korean and Indonesian colleagues to begin the following academic year. This undertaking has profound implications in the way faculty and students will frame their teaching and studies; but also, now that the participation of Professor Michael Herzfeld from Harvard University as IIAS Visiting Professor has been confirmed, a continuing dialogic platform will be established, involving language-based and/or historically knowledgeable scholars. This model will contribute, in a truly contextualised fashion, to the study of the production of cultural knowledge – ‘heritage’ – and its contemporary uses. It is a challenge that the universities mentioned above have been willing to take on, with the additional objective of engaging their societies and peoples in the whole debate over culture and identity, at home and in relation to ‘others’. In parallel to these two initiatives in the field of heritage, IIAS continues to help local partners in organising in situ roundtables where representatives of the civil society, local authorities and local universities are engaged in the revitalisation of an urban area. These events are usually developed in collaboration with UKNA members or affiliates (Urban Knowledge Network Asia, www.ukna.asia). The most recent roundtable took place in Macau, with a special focus on the city/port and now Special Administrative Region’s ‘Inner Harbour’ (Portuguese: Porto Interior, Chinese: 内港). The area represents one of the oldest points of contact between China and Europe and was, for at least two centuries, the only allowed centre of commerce between the Empire and the rest of the world. The roundtable was organised in collaboration with the Institute of European Studies of Macau, Macau University, the SAR’s Cultural Bureau and local civil society actors. It took place prior to IIAS’s Winter School, this time in collaboration with Macau University, on the theme of ‘Urban Hybridity in the Post-Colonial Age’ (16-20 Dec 2013). The co-conveners were Michael Herzfeld, Akhil Gupta and Engseng Ho, with the participation of Tim Simpson, Jose Luis Sales Marques and Non Arkaraprasertkul. This Winter School, with twenty-six participants and twentyone nationalities, proved to be one of the best ever organised by IIAS. We are now preparing the upcoming heritage-related Summer School, to be held in Chiang Mai next August, this time on ‘Craft and Power’, in collaboration with Chiang Mai University, and with the participation of Achar Chayan, Aarti Kawlra, Pamela Smith and Françoise Vergès. The Summer School, made possible by a grant from the Mellon Foundation, will be followed by an in situ roundtable with textile weaving communities. Relevant to all our activities, including the IIAS Summer/ Winter Schools, is the continued collaboration with Asian partners, to further anchor IIAS and its network at the core of knowledge-making in and on Asia.

The Newsletter and IIAS The International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS) is a post-doctoral research centre based in the Netherlands. IIAS encourages the multi-disciplinary and comparative study of Asia and promotes national and international cooperation.

IIAS Main Office International Institute for Asian Studies PO Box 9500 2300 RA Leiden The Netherlands

The Newsletter is a free quarterly publication by IIAS. As well as being a window into the institute, The Newsletter also links IIAS with the community of Asia scholars and the worldwide public interested in Asia and Asian studies. The Newsletter bridges the gap between specialist knowledge and public discourse, and continues to serve as a forum for scholars to share research, commentary and opinion with colleagues in academia and beyond.

www.iias.nl

IIAS Photo Contest 2014: Picturing Asia Upload your photos now Have you submitted your photos yet? There is still time to enter. You have until midnight 30 June 2014 (CET).

Vote for your favourite Make sure to visit the IIAS Photo Contest page on www.flickr.com between 1 and 29 Aug 2014, where you will be able to vote for your favourite photos. The photo that has been marked as a “favourite” by the most people will be announced the winner of the Public Vote.

Seven prizes worth 200 euro There will be one winner for each of the six Categories (selected by the jury) and one winner of the Public Vote. Each prize will be a gift voucher (from various online shops) for the amount of 200 Euro. Prizes will be transferred to each winner by post or email. All winners (Category and Public Vote winners) will be announced on Monday 1 Sept 2014. Announcements will be made on the Photo Contest website, as well as the IIAS website along with our social media sites on Flickr, Facebook and Twitter. The October issue of The Newsletter (#69) will also feature the Photo Contest, the winners, and their winning photographs. Find all the information you need to compete and/or vote at

www.iias.nl/photocontest Please do read the rules and regulations before submitting. Good luck to everyone!!!

Asian Cities Global Asia Asian Heritages Asia’s Pop Culture Everyday Life in Asia Asia by Mobile

We ask you to send in a maximum of 5 photographs per person, for any combination of the 6 categories above (find a description of each category on the contest site)

Philippe Peycam, Director IIAS

Visitors Rapenburg 59 Leiden T +31 (0) 71-527 2227 F +31 (0) 71-527 4162 iias@iias.nl

Colophon The Newsletter #68 Summer 2014 Managing editor: Sonja Zweegers Guest editors for The Focus: Fridus Steijlen and Bart Barendregt Regional editor: Terence Chong (ISEAS) The Network pages editor: Sandra Dehue Digital issue editor: Thomas Voorter Design: Paul Oram Printing: Nieuwsdruk Nederland Submissions Deadline for drafts for Issue # 69 is 15 July 2014 Deadline for drafts for Issue # 70 is 15 November 2014 Deadline for drafts for Issue # 71 is 20 March 2015 Submissions and enquiries: iiasnews@iias.nl More information: www.iias.nl/publications

Subscriptions For a free subscription: www.iias.nl/subscribe To unsubscribe, to make changes (e.g., new address), or to order multiple copies: iiasnews@iias.nl Rights Responsibility for copyrights and for facts and opinions expressed in this publication rests exclusively with authors. Their interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views of the institute or its supporters. Reprints only with permission from the author and The Newsletter editor (iiasnews@iias.nl).

Daniel Foster/flickr

I WILL DISCUSS HERE some developments within the Asian Heritages cluster, as the last six months have seen a number of projects taking a more solid if not institutionalised form, while more events took place or are being scheduled: a series of conferences on heritage politics in Southeast and East Asia, in collaboration with the Inst. for Southeast Asian Studies and Academia Sinica; the formalisation of a graduate teaching programme at Leiden University, and from Sept 2014, at National Taiwan University; and the continuation of the in situ roundtable series now in conjunction with IIAS Summer/Winter Schools. Before I do that, I would like say something about the first Africa-based conference on Asian studies that IIAS, through the ICAS Secretariat, is helping to organise in collaboration with the Association for Asian Studies in Africa (A-ASIA) next year. This international conference entitled ‘Asian Studies in Africa: Challenges and Prospects of a New Axis of Intellectual Interactions’, will be held in Accra, Ghana, on 15-17 January 2015. It will be an event of historical magnitude for what it means in terms of long term development of a corridor of intellectual, academic and cultural exchanges between the two continents. I would like to thank the numerous people and institutions in Africa, Asia, the United States and Europe who have expressed interest in participating in this pioneering event, and those who are supporting it. We have been amazed by the number of paper and panel abstracts already submitted and by some fascinating ideas that have emerged for proposed roundtables. This enthusiasm is shared by people from US Liberal Arts colleges to prestigious academic centres in Senegal, India, Ethiopia, China and Southeast Asian countries. It shows that a real ‘axis of knowledge’ between Asia and Africa has now become a necessity. In anticipation to the Accra conference, I want to, on behalf of the organising committee, express my gratitude and satisfaction (for more information about the conference: www.africas.asia). I am returning to Heritage. Heritage as a discourse corresponds to the rise of the modern nation-state and its formulation is constitutive to the nation-making ‘project’. Yet, heritage is signified and produced as a result of a complex process of power relations involving social actors such as the state, local communities, activists, and civil society organisations – including universities – as well as international/interstate entities such as UNESCO, Asian Development Bank, ASEAN, etc. To address the complexity of this power relation, IIAS, ISEAS and Academia Sinica decided to explore the role of these social actors in context, and in their interactions with each other. The first conference took place in Singapore in January 2014, focusing on the role of the state. It was a great success, especially given the choice taken by the host partners, ISEAS and National University of Singapore, to juxtapose situations occurring in various countries with that prevailing in Singapore, particularly in the aftermath of the planned destruction by the Government of the Bukit Brown Cemetery. The second event is to be held in Taiwan in December 2014. It will focus on the role of citizens, local communities and civil society organisations in heritage-making. It promises to be another landmark event, largely because of the vibrancy of Taiwan’s civil society. The third meeting will most likely take place in the Netherlands toward the end of 2015, and will focus on the role of international organisations and global heritage activism. Each of the events will result in a collective edited reference volume.

The Newsletter | No.68 | Summer 2014

4 | The Study

Bali at war: a painted story of resistance to colonial rule The defeat of the royal family in Klungkung by Dutch soldiers on 28 April 1908 marks the point at which the entire island of Bali was incorporated into the colonial administration of the Netherlands East Indies. Both the event and the painting discussed here are known as the Puputan, meaning the ‘finishing’ or ‘the end’ in Balinese, referring to the slaughter or ritual surrender of the Klungkung royal family. This painting sits within a corpus of oral traditions about the defeat of Klungkung yet it shifts conventional perspectives by describing local developments prior to the clash between the Dutch and members of the royal household at the site of the palace.1 Siobhan Campbell

Entertaining the gods The painting comes from Kamasan, a village of four-thousand people located between the east coast and the mountain ranges of Gunung Agung in the district of Klungkung in Bali. Formerly Klungkung was the seat of royal power, home to the court of the Dewa Agung, the preeminent ruler of Bali. Kamasan village is made up of wards (banjar) reflecting the specialised services once provided by artisans to the court, including goldsmiths (pande mas), smiths (pande) and painters (sangging). Kamasan paintings depict stories from epics of Indian and indigenous origin, relating the lives of the deities, the royal courts and sometimes even commoner families. Narratives serve a didactic and devotional function and are intended to gratify and entertain the gods during their visits to the temple, as well as the human participants in ritual activities. Paintings were once found in temples and royal courts all around Bali and these days paintings circulate in many different contexts including private homes, government offices and museums. Kamasan art is highly conventionalised in that artists work according to certain parameters (pakem) and adhere to strict proscriptions in terms of iconography.2 Their paintings are sometimes called wayang paintings with reference to shared roots with the shadow-puppet (wayang) theatre. Artists also refer to the figures they paint as wayang, which are depicted in almost the same manner as flat Balinese shadow-puppets except in three-quarter view. While artists interpret the stylistic and narrative boundaries of this tradition in different ways, they maintain that they belong to an unchanging tradition of great antiquity. Artist Mangku Mura (1920-1999) is one of the most well-known Kamasan artists of the twentieth century. He was posthumously recognised by the Indonesian government in 2011 with an award for the preservation and promotion of traditional art. Unlike most Kamasan artists, who descend from a core line of painting ancestry, Mangku Mura comes from outside the ward of painters, but learnt to paint as a teenager by studying with several older village artists. Of his seven children, Mangku Mura nominated his sixth child, Mangku Nengah Muriati (born 1966), as his successor and both have produced several versions of the puputan story. Mangku Mura produced the first version of this painting in 1984 shortly after the initiation of an annual ceremony to commemorate the puputan. It was commissioned by the head (bupati) of Klungkung district who was also a member of the royal family. The episodes depicted are based on an oral version of events related to Mangku Mura by his grandfather Kaki Rungking, said to have been an eyewitness to much of the action. In turn, Mangku Mura passed the story on to members of his immediate family, including his daughter

Mangku Muriati. Demonstrating how paintings gain additional layers of meaning through elucidation of the story, Mangku Muriati explained that Kaki Rungking had a connection to the royal court which is not mentioned in the painting – his sister was an unofficial wife (selir) to the Dewa Agung and lived in the Klungkung palace. This connection was emphasised to explain how Kaki Rungking knew of the broader sequence of events and to establish his credentials as a witness. The artists have also ensured that specific details are communicated without ambiguity by incorporating textual narrative in each scene, written in Balinese script (aksara). Sacred heirlooms The painting is divided into ten scenes over four horizontal rows. From the perspective of the viewer, the story moves chronologically from left to right beginning in the bottom left-hand corner and finishing in the top right-hand corner. The text in the first scene relates the movements of the Dutch soldiers, depicted as six uniformed men carrying muskets. Having landed at Kusamba, they passed through Sampalan along the bank of the Unda River. They continued towards the Pejeg burial ground (setra) and on to Tangkas. Finding nobody in Tangkas they kept moving towards the home of Ida Bagus Jumpung in Kamasan. He was the guardian of an heirloom dagger or kris (pajenengan) belonging to the Klungkung royal family, which the Dutch planned to capture. In the second scene there is a discussion between Ida Bagus Jumpung and his wife. The tree between them is a standard convention when two parties are facing one another in conversation or confrontation. Ida Bagus Jumpung is holding the heirloom and is accompanied by a retainer. Two females accompany his wife. Ida Bagus Jumpung is informing the women that he has been entrusted to safeguard the important regalia. In the third scene the Dutch troops have reached the gateway of the priestly compound. They kill Ida Bagus Jumpung. As they seize the heirloom his corpse mysteriously disappears, so Ida Bagus Jumpung is not depicted in this scene. There are only two Dutch officers; they aim their muskets at the closed doors of the compound gateway (paduraksa), guarded by a pair of dogs. The latter two scenes emphasise the connections between the royal regalia and the ruling dynasty; the loss of sacred heirlooms also foretold the defeat of earlier Balinese dynasties.3 Here the capture of the kris is a sign that defeat was imminent. The fourth scene begins on the next row as the Dutch troops arrive at the Gelgel palace. This palace was re-established as a branch line of the Klungkung royal family during the reign of Dewa Agung Madia (1722-1736). There is a lone guard, a resident of Pasinggahan, standing on duty outside the palace. He is shot dead. The other guards are eating rice cakes (tipat) in the courtyard, a detail related only in the text. They are all shot down as the troops enter the palace.

Above: Mangku Muriati applying black ink to the eyes of the Dutch troops, Kamasan 2011. Right: The site of the former royal palace in Klungkung today. Below: Mangku Muriati reciting the story from a version made by Mangku Mura in 1995, Kamasan 2011.

Protecting the Gelgel palace The plump figure of Kaki Rungking (grandfather of Mangku Mura) appears for the first time in the next scene. He witnessed the slaughter of the guards and covertly assembled his own weapon. It is mounted on a waist-high stand but is otherwise of similar appearance to the muskets held by the Dutch officers. Firing one shot, his bullet kills a lieutenant. His left hand rests on his hip and the thumb and index finger of his raised right hand are held together in the same gesture of defiance adopted by the Balinese figures in other scenes. Despite the show of bravado in his visual depiction, the text relates that Kaki Rungking was terrified to find himself all alone. He ran for cover as the Gelgel palace was destroyed around him. The people of Jero Kapal, where the palace is located, also ran away to avoid being shot. This is the only scene in which Kaki Rungking is depicted visually. His position in the centre of the composition highlights his role as protagonist. Iconographically, little distinguishes him from the commoner figures in other scenes. All have thickset bodies, hairy torsos, dark skin, wavy hair and short loincloths with less ornate head-dresses and clothing than the nobles. Kaki Rungking’s gallantry is reinforced by a detail in the text. It states that the target of his fatal shot was an officer of rank. By appearance alone the lieutenant is no different from his fellow officers, except that a chain binds his dead body. In fact, the only apparent difference between all of the colonial officers is their eyes. Most have the type of rounded (bulat) eyes associated with demons though a few officers have the same wavy (sipit) eyes as the commoners. This might refer to the composition of the colonial forces, which comprised both Dutch and indigenous officers. In relation to the veracity of Kaki Rungking’s role, it is worth noting that the death of a Dutch lieutenant and his officers did occur in the fortnight prior to the massacre during a routine inspection of the opium monopoly at Gelgel. The incident resulted in raised hostilities between Klungkung and the Dutch.

The Newsletter | No.68 | Summer 2014

Treachery The third row, scene six, begins with the Dutch troops moving towards Tojan. They spent the night in a village called Carikdesa, the present-day site of Galiran market. While the troops were resting a commoner from Lekok appeared with a kris but was killed before he could attack. In scene seven, the text explains that key figures from the Gelgel palace went to Klungkung to discuss the critical situation with the king Dewa Agung Jambe. The lords of Gelgel were obstinately opposed to the Dutch. The father of the Dewa Agung is shown standing on the right with two servants seated in front of him.4 He advised the Dewa Agung that Klungkung must not surrender and that as nobles (satria) they must prepare to die. The Dewa Agung, on the left, is in the company of three women of the royal household whose different ranks are marked by their headdresses. Traitors to the palace are depicted in the eighth scene, including the figure of a brahmana, a commoner (kaula) and a Muslim. The text explains that a lord (cokorda) was also secretly cooperating with the Dutch because he hoped to take over the role of the Dewa Agung. Mangku Muriati advised that when her father was initially commissioned to produce the painting he was instructed not to write the actual names of these traitors on the painting, even though they were known. The action continues around the Klungkung palace in the ninth scene on the top row. The confrontation took place in the palace forecourt (bencingah) as the Dutch arrived from the south. Cokorda Bima attacked the Dutch; his loyalty to the Dewa Agung so great that when he lost his right hand he picked it up, tucked the limb into his waist-cloth and continued to fight with his left. The illustration shows him standing in the centre of his fallen comrades before he too is killed. Only a small child was left alive, buried under the dead, Dewa Agung Oka Geg (1896-1965), the eldest son of Dewa Agung Smarabawa, a half-brother of the Dewa Agung and the second-king (iwaraja). Despite being shot in the foot, he survived because a Dutch soldier, visible amongst the Balinese corpses, took pity on him. This detail tallies with other official versions, however, some Balinese accounts relate that the child was stabbed by other

The Study | 5

Above: Mangku Muriati, Puputan

Klungkung, 2011, acrylic and natural pigment on cotton cloth.

Balinese. The text of the tenth and final scene describes four treacherous lords from Akah, Manuang, Aan and Klungkung. They had hoped to benefit from a Dutch victory; instead they were exiled to Lombok and ordered to raise the surviving child. An adult Dewa Agung is depicted sitting on a pedestal on the right-hand side, separated from the three lords by a tree. Reversing conventional representation The Dewa Agung Oka Geg did return to Klungkung as an adult. He served various administrative functions within the colonial bureaucracy, including as clerk, inspector of roads (mantri jalan) and roaming official (punggawa keliling) to the Dutch administrator. In 1929 the Dutch Resident of Bali and Lombok swore him in as Dewa Agung of Klungkung at the state temple in Gelgel. In 1938 all eight of Bali’s regents were given the title ‘autonomous ruler’ (zelfbestuurder) in a ceremony at Besakih. Formally, this placed the Dewa Agung of Klungkung on the same footing as the rulers of other kingdoms. However, by the 1940s the Dewa Agung was “probably the largest landowner of all the kings, and certainly the most powerful.”5 Mangku Muriati commented that Dewa Agung Oka Geg was so powerful (sakti) that even the Dutch spared his life when they could have destroyed the royal family for good. Although the visual presence of Kaki Rungking attests to the immediacy and integrity of the story, the story gains further elaboration with each retelling. Like some Balinese literary accounts of the puputan by the ruling families of Badung in 1906, the painting combines historical details, personal memory and conjecture.6 The most remarkable aspect of the painting is the way Mangku Mura embedded his ancestor in the centre of this historical moment. It is unusual for a commoner to take the leading role in a story commonly associated with the Balinese courts. Though Kaki Rungking is protagonist and story narrator, in the painting he appears alongside various commoners (jaba). Some loyally served and defended their social superiors, while others conspired against the royal family. Not only did Mangku Mura reverse conventional representation by giving the leading role to a commoner, he emphasised the disunity amongst the

Balinese themselves in their opposition to colonial rule. Given the role that the puputan plays in Indonesian national histories as a symbol of resistance this was probably the most subaltern position of all, disrupting conventionally conceived histories of the conflict between colonial and indigenous subjects. Siobhan Campbell, Department of Indonesian Studies, The University of Sydney. Siobhan spent six months as an IIAS postdoctoral fellow researching collections of Balinese art in the Netherlands in 2013-14. (siobhan.campbell@sydney.edu.au) References 1 These are the subject of an extensive study by Wiener, M.J. 1995. Visible and Invisible Realms: Power, Magic, and Colonial Conquest in Bali, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Wiener was doing research in Klungkung when Mangku Mura initially produced this narrative; after seeing his painting displayed in the office of the district head of Klungkung she commissioned a version of the painting, which became the cover illustration for her book. 2 Refer to Vickers, A. 2012. Balinese Art: Paintings and Drawings of Bali 1800-2012, Singapore: Tuttle. 3 For instance when Anglurah Agung ousted Dalem di Made from his palace in Gelgel many of his retinue returned to their own homes taking their powerful and sacred heirlooms with them. See Creese, H. 1991. ‘Balinese Babad as Historical Sources: A Reinterpretation of the Fall of Gelgel’, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 147(2/3): 236-260, Leiden: BRILL, KITLV (http://tinyurl.com/balinese-babad) 4 The birth father of Dewa Agung Jambe was Dewa Agung Putra III who died in 1903. On this point the text of the painting is not necessarily incorrect as the reference to father might be taken to imply the close relationship between Dewa Agung Jambe and the Gelgel palace. 5 See Vickers, A. 1989. Bali, a Paradise Created. Rowville, Ringwood: Penguin, p.139. 6 See Creese, H. 2006. ‘A Puputan Tale: “The Story of a Pregnant Woman”,’ Indonesia vol.82, Oct 2006, p.82. (http://tinyurl.com/ puputan-tale)

The Newsletter | No.68 | Summer 2014

6 | The Study

Learning from Hong Kong: ‘place’ as relation The Hong Kong-China border is slowly dissolving. In 2010 a part of the frontier area at Lok Ma Chau opened up for new urban developments. By 2047, 50 years after the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to China, the border will no longer exist. This project proposes an inhabited bridge at Lok Ma Chau, connecting Hong Kong and Shenzhen, that recognises both the global movement within the Pearl River Delta as well as the local sense of ‘place’. In an attempt to learn from Hong Kong I ask: What makes place in Hong Kong valuable? What is the influence of globalisation on the local experience of place other than ‘placelessness’? And how as designers can we work with this? Renske Maria van Dam

Above: Cross section of the inhabited bridge connecting Hong Kong (left) and Shenzhen (right). Below: Model pictures of the three atmospheres.

Placelessness The Pearl River Delta is characterised by the intense movement between cultural, political and environmental differences. Due to Hong Kong’s history as a British colony and its recent transformation into one of the most important global urban agglomerations connecting Eastern and Western economies, the Pearl River Delta has become a space of transit. At Lok Ma Chau this is clearly visible in the urban fabric. The landscape is dominated by huge infrastructural elements that facilitate the transit between Hong Kong’s wealthy economy, with its beautiful wetlands along the borderland, and China’s cheap labour industry with standardised high rises. In contemporary urban theory this sense of movement, the result of the parallel existence of differences, is often understood as a problem rather than a quality, resulting in the experience of ‘placelessness’. In this theory, the movement and the clash of differences are reflected in an accumulation and intersection of parallel urban atmospheres that prevent a local sense of place. As a reaction to this general shunning of place the question of a new sense of place arises. This often leads to a nostalgic desire for a traditional sense of place that is still visible in some historical villages, suggesting that the emergence of the modern metropolis has been a mistake. But, in contradiction to contemporary urban theory, ‘place’ in Hong Kong is valuable. Not only in an absolute sense, reflected in the high land-prices, but also in an emotional sense as acknowledged by its visitors and inhabitants. In Hong Kong there is, despite the movement and differences, a possibility to experience what I call: a sense of place within movement. Place as relation To understand the valuable sense of place within movement in Hong Kong, place has to be valued as a dynamic intangible singularity rather than as tangible object or reified identity. In other words place should be understood as relation. A juxtaposition of Western and Eastern conceptions of space helped formulate this conclusion. Whereas Western place-conceptions are formed on object-based networks, the Eastern conception of place is based on relationality through movement manifested in the use of voids. One of the most helpful concepts to understand this quality of place, as a dynamic intangible relationship, is the Chinese bagua. The bagua are eight ‘trigrams’(symbols comprising three parallel lines, either ‘broken’ or ‘unbroken’, representing yin or yang respectively – signifying the relationships between the five elements: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water), which are often portrayed around a centrally placed yin-yang symbol, believed to have a void in its middle. This void is not empty, but filled with energy; relational movement between the elements. The bagua can be used as a ‘map’ to align all the elements in, for example, a house. The traditional Chinese courtyard is also an exemplary manifestation of this philosophy.

Thus the seemingly problematic context of movement and differences has potential. Hong Kong cannot be described by differences such as east or west, tradition or modernity, global or local, but the valuable Hong Kong place experience is one in which the differences between its parts cause a delicate and sensitive relationship and therefore a new sense of place; a sense of place within movement. Personages If place is understood as relation, as designers we not only have to engage with the physical qualities of place, but we also have to engage with the intangible qualities of place. We have to design for resonance. Resonance can be understood as emotional ‘vibration’ that is achieved by stimulation of latent experiences. Where the embodied experience of touching ice might cause a temporary cold feeling in your fingertips, the emotional response, the resonance, may be formed by means of transversal association; for example, previous personal or culturally based experiences, or even future dreams. Just like music instruments that, without being touched, vibrate in sympathy with another instrument being played at that moment; we too interact with our environment in this way. To include latent experiences into the design process, I developed five personages, based on associative questionnaires taken with the potential future users. In short: 1) a school child living in Shenzhen and who crosses the border twice every day to go to school; 2) a businessman living in Hong Kong and who crosses the border at least twice a week to do business in the Pearl River Delta; 3) a migrant who crosses the border only during Chinese holidays to visit his family still in China; 4) a tourist who crosses the border for leisure purposes to see the Hong Kong cultural highlights; 5) a local living in the frontier area, who currently never crosses the border, but who might find a job in the developing borderland eco-tourism in the future. These personages inspired a design of three atmospheres (see below) that, defined by kinaesthetic differences, engage with a relational void, global and local program and the surroundings of the borderland. Atmospheres An atmosphere is a strong potential of a place that can influence one’s feelings and is achieved by carefully designing for all the senses. Just like specific colours in paintings will stimulate specific emotions, the use of specific architectural elements will stimulate the experience of specific atmospheres. The first atmosphere is inspired by the fast economic connection between Hong Kong and China and facilitates the users who will cross the border on a daily basis or visit for shopping. The energy is directive and commercially oriented. The second atmosphere is inspired by the leisurely connection

between Hong Kong and China. It facilitates the users who wander around the region visiting various kinds of tourist facilities. The energy is associative and educationally oriented. This atmosphere houses tourist information points and a historical museum. The third atmosphere is inspired by the local landscape and is designed as a place to enjoy nature and relax. It facilitates a natural walking route and the offices related to the border-control function. Bridge in difference The final design is for an inhabited bridge based on these three atmospheres that swirl through and around a long ‘void’ that literary and symbolically connects Hong Kong and China. This relational void, as inspired by the ancient Chinese bagua, links the atmospheres to each other and to the surrounding landscape. The quality of the relational void is further developed in the inner and outer façades. The rhythm of the inner void interacts with the rhythm of the outer routes in such a way that the experience of place within movement is further stimulated by the effect of anamorphosis. And the swirl of the outer routes takes the bagua concept literary by turning the experience of its architectural elements upside-down; roof becomes façade becomes floor. In this way, what might be valuable (a specific view or experience) for one person, might be insignificant for others. Thus, by means of different speeds and purposes the bridge will become place and movement simultaneously. The Lok Ma Chau bridge therefore becomes a place to not only move through, but also to go to, and thus provides a sense of place within movement. Learning from Hong Kong Hong Kong inspired me to understand ‘place’ as relation instead of object. This opened up my thinking towards a different understanding of architecture. It also encouraged me to enrich my approach to design from a very rational, pre-determined design process to an open-ended one, based on trial and error. This project gave me the chance to work with a concept that is, in my opinion, highly valuable for contemporary society: an understanding of place as relation. It is my aim to develop this understanding of place and resonance in future research and design, since there is still much more to learn from Hong Kong. Renske Maria van Dam is currently working as an architect for her own atelier SPICES and as researcher at ALEPH (autonomous laboratory for exploration of progressive heuristics currently residing at the Royal Academy of Arts, the Hague) where she is preparing a PhD project on ‘the mechanism of non-local resonance in the experience and design or place’. (renskemaria@gmail.com)

The Newsletter | No.68 | Summer 2014

The Study | 7

‘Home and Away’: female transnational professionals in Hong Kong Mobility has become a buzzword of our times. There is an increased sense that we are no longer constrained to live in one place throughout our lives, or even in one place at a time. Indeed, there is now a growing body of literature that advocates the concept of transnational mobility to make sense of the new fluid living patterns, the affective and instrumental relationships that cross national borders and span localities, and the conceptualisations of transnational ‘lifespaces’1 within the broader perspective of pluri-local attachments in late modern society. Maggy Lee

TRANSNATIONAL PROFESSIONALS are part of this broader trend of mobile people moving either part-time or full-time, temporarily or permanently. These ‘transnational elites’ – a term used to refer to the highly skilled professionals in global cities2 – have been described as the archetypal transmigrant, the nomadic worker, the embodiment of a new cosmopolitan identity in cross-border spaces. They are able to take advantage of the flexibility in global labour markets, the ability to live and work in different places, and with these, increased leisure time in affluent societies, extended holidays, and flexible working lives. Yet we know relatively little about their motivations and actual experiences. Apart from a few notable exceptions,3 there is relatively little sociological work on what transnational mobility means for female expatriate professionals. Does it bring about greater freedom and security or social exclusion, improved or weakened social and financial status, better career prospects or new constraints? Our two-year research study, ‘Home and Away: Female Transnational Professionals in Hong Kong’,4 looks at what transnational mobility means for female expatriate professionals, how and why they move from one place to another and under which conditions, their needs and aspirations, and the advantages and disadvantages of their mobile lives. The study involves in-depth interviews with forty highly educated, highly skilled female transnational professionals who relocated to Hong Kong either as lead migrants or as accompanying spouses on a dependent visa. The forty interviewees cover a broad spectrum in terms of age, Western and non-Western nationalities, employment status and sectors in which they or their partners work. About two-thirds were married at the time of interview. Their length of residence in Hong Kong varies from three months to thirty years. We used snowball sampling as well as a number of social institutions, non-governmental organisations, residential forums, internet-based blogs and expatriate websites as our recruitment sources. The interviews were conducted face-to-face, typically in coffee shops or the university campus; a number of respondents even welcomed us into their home or workplace to share their stories. Meaning and practices of mobility What is striking about these female transnational professionals is the extent of their mobility and how much this features as an integral part of their individual biography. Over half of the respondents have studied, lived and/or worked in other countries prior to relocating to Hong Kong. Their stories are full of intersecting forms of mobility and vivid memories of travel - for example, growing up as a child with parents with a history of military or missionary postings, backpacking and travelling for pleasure, working as au pairs or on overseas

postings, studying as exchange or research students. Some respondents kept moving in order to stay close to the family at different stages of their life course. For example, one interviewee was born in France, moved to Gabon in Africa with her parents at the age of two, finished her high school in Madagascar and university degree in France, lived and worked in Beijing and Switzerland before relocating to Hong Kong with her husband and their children. Economic and non-economic motivations For many respondents, relocation to Hong Kong depends heavily on financial and career considerations and is perceived as part of a career advancement strategy for themselves or their partners/spouses. It involves obtaining employment opportunities and professional experiences that would otherwise be difficult to come by. Although perceptions of economic opportunities prevail across different cohorts, the conditions of possibility for female expatriates have been shaped by the changing socio-economic conditions, state policies and Hong Kong’s colonial legacy and development as an international centre for global business and finance. Transnational professionals who are now coming towards the end of their working lives set out on their overseas careers in very different social and political environments. Single women who arrived during the era of colonialism and Hong Kong’s rapid economic expansion in the 1980s encountered relatively few immigration restrictions and employment barriers. Most were able to secure job offers with high remuneration and tended to describe their relocation to Hong Kong as empowering and life-changing. One British respondent who joined the local civil service before the recruitment of expatriates officially ended in the mid-1980s recalled her excitement and sense of adventure when she was recruited to work in the legal department without having to retake any examinations: “The government paid for my business class flight. I was twenty-five. They did everything for me and gave me a serviced apartment. I got paid HK$16,000 a month. It was an amazing deal.” In contrast, women who arrived in postcolonial Hong Kong have to navigate increasingly restrictive immigration policies and economic uncertainties. As one respondent explained, she had ‘a fantastic time’ as a single woman working as a pre-school teacher in Hong Kong when she was recruited by an international company in the early 2000s. However, her experiences during a second relocation with her unmarried partner on international transfer and their son were far less positive. The combined effects of her visitor status and visa restriction meant she could not seek part-time employment, open a bank account or join the local library, and she was constantly fearful that her tourist visa would not be renewed.

Our study demonstrates the continued importance of understanding how female transnational professionals negotiate their mobilities and moorings and the gendered effects of transience on individuals and families today.

Besides economic motivations, many respondents aspire to enhance social freedom and to break constrictive gender roles and family life through their spatial mobility. This is particularly evident amongst single women who spoke of their new lifestyle in terms of new beginnings and self-development as their status changes from being a student or self-initiated mover to a highly skilled transnational professional. Their relocation has enhanced their ability to be more self-confident and enabled them to clear their student debts: “I love my family dearly, but I found that I was doing things for them rather than thinking about myself. In Hong Kong I am doing everything for me. I have just started Mandarin classes. I am looking to join a choir or something so I can meet other people. I travel a lot using my own savings. It’s all very liberating!” Gender matters Nevertheless the empowering possibilities of leading an itinerant lifestyle often go hand in hand with less positive feelings of loneliness and loss, of being unable to attend important occasions in the lives of family and friends (e.g., birthdays, christenings), of children growing up in the absence of grandparents and cousins. Seen in this light, transnational mobility involves both continuities and discontinuities, being able to embrace some sort of freedom while retaining certain social connections. Furthermore, their freedom from constraints and obligations is tempered by gendered expectations. This is particularly evident in the stories of accompanying spouses with children. Although many described shouldering a reduced burden of domestic labour in the expatriate household, this is almost always achieved through outsourcing household and childcare labour (e.g., employing live-in domestic migrant workers) rather than through renegotiation of gendered roles and practices. Others described or anticipated the obligation and stress of caring for elderly parents or parents with health problems especially in the current era of global austerity. For many respondents, the focus of social interactions and leisure spaces tend to be shaped by their life course – revolving around colleagues, travel and the pub focus of expatriate life among single women, and around children and their school activities among accompanying spouses. This means women who do not fit into these categories can feel particularly vulnerable and socially isolated. Accompanying spouses who put their career on hold spoke of the practical and emotional challenges they face, frustrations of losing their financial independence and sense of identity, and the extra efforts required to lead an independent social life: “Back home where I grew up, people know me all my life. I have been a professional, so I am who I am … Here, everything works around my husband. I want my husband to be better experienced and so on. But financially, I am insecure. In the past I knew that I have complete ownership of my income. Now even if my husband gives me money, I am not so sure if I want to go ahead to buy a pastry for myself because I am so used to enjoying my own money.” Negotiating mobilities Our respondents’ stories highlight the ongoing nature of migratory plans as highly skilled transnational professionals make continuous decisions to relocate, cut short or extend their stay, leave and then return to Hong Kong, often in the context of practising mobility as a family project. Although many women feel empowered by their mobile lives, there are still concerns about the persistent constraints of professional women’s social lives and how these are exacerbated when the husband’s career necessitates or precipitates the move abroad. Our study demonstrates the continued importance of understanding how female transnational professionals negotiate their mobilities and moorings and the gendered effects of transience on individuals and families today. Maggy Lee, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, The University of Hong Kong. (leesym@hkucc.hku.hk)

References 1 Robins, K. (ed.) 2006. The Challenge of Transcultural Diversities, Strasbourg: Culture and Culture Heritage Department, Council of Europe. 2 Beaverstock, J. V. 2005. ‘Transnational Elites in the City: British Highly-Skilled Inter-Company Transferees in New York City’s Financial District’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31(2): 245-268. 3 Coles, A. & A.M. Fechter (eds) 2008. Gender and Family among Transnational Professionals, London: Routledge; Geoforum. 2005. ‘Special Issue on Gender and Skilled Migration’, Geoforum 36(2); Kofman, E. & P. Raghuram. 2006. ‘Gender and global labour migrations: Incorporating skilled workers’, Antipode, 38: 282-303; Yeoh, B. & K. Willis. 2005. ‘Singaporeans in China: transnational women elites and the negotiation of gendered identities’, Geoforum, 36: 211-222. 4 The project ‘Home and Away: Female Transnational Professionals in Hong Kong’ (HKU7011-PPR-11) is funded by the University Grants Committee under the Public Policy Research programme.

The Newsletter | No.68 | Summer 2014

8 | The Study

‘Silence is the best solution’ This study surveys the Dutch (military) strategy versus the media, during the conflict with the Republic of Indonesia between 1945 and 1949.1 The Dutch (military) information services in Batavia had been slow to establish itself, and only a limited number of Dutch reporters and photographers were located in the capital. There was talk of embedded journalism; the majority of Dutch reporters stayed mostly in their comfort zone, never left their hotels in the centre of Batavia, visited receptions and press conferences and received their information via the diplomatic circuit, from briefings and the communiqués issued by the military and government information services. They were frequently hindered in their newsgathering, fact checking and the reporting of both sides, and if they did travel into the relatively unsafe conflict areas on Java and Sumatra they were accompanied by press officers. Louis Zweers

1 PRESS CENSORSHIP, which led to a regulatory self-control among journalists, made it almost impossible for them to file critical pieces with their editors. It was difficult to escape the coercion and interference of the employees of the information services. The journalistic output of the majority of reporters, whose gaze was rather clouded by propaganda, served to legitimate Dutch military action. At that time, many Dutch journalists were generally obedient, the media was pillarised, and many national newspapers were just mouthpieces for political parties. The pro-government media behaved compliantly and the tone was reassuring. It appeared as if a silent agreement had been made: we shall not reveal all. Over time, more and more (international) journalists and photographers arrived in this conflict area. Unlike the embedded Dutch journalists, these experienced foreign correspondents were not easily intimidated by the (military) information services, and routinely reported on the Indonesian independence struggle. The information authorities, as a result, dismissed the foreign press corps in Batavia as a nuisance, hacks on the payroll of – in their eyes – anti-colonial British and American authorities and media. Communications war During the first military action (July/August 1947) those press people considered to be reliable were given permission to join the advancing Dutch troops on Java and Sumatra. The information organisations were hereby not only managing the news, but at this point were also increasingly controlling the photo coverage of the war. Journalists and photographers were becoming ever more dependent on the cooperation of the information services. The majority of published photos and news reports of selected events of the war were ideologically coloured and gave a scripted version of reality. The communications war was an unequal struggle between the various information services and the Dutch media; especially for the left-wing newspapers and magazines such as Het Parool, Vrij Nederland, De Groene Amsterdammer and the communist De Waarheid, which had only limited financial resources and opportunities. The opposition to the colonial war remained limited to these media outlets, which, due to a lack of funds, did not have their own correspondents and photographers stationed in the archipelago. Moreover, many of the left-wing daily and

weekly newspapers, critical of the Dutch policy in Indonesia, were banned for readers in the military, and often not even distributed in Batavia. These papers certainly did leave their own mark on the (photo)reporting about the Indonesian question. They were critical and even fiercely pro-Indonesian, but only about a quarter of the population actually read these relatively negative reports. Thousands of former Het Parool and Vrij Nederland readers appeared unappreciative of such critical and negative reporting, and the papers saw their subscription numbers drop rapidly. There was a lot of verbal aggression in the press. The critical press was dismissed as fellow travellers and even as ‘friends of Sukarno’ by Elseviers Weekblad and Trouw, which functioned as mouthpieces for the colonial-thinking Netherlands. This conservative media accused them of using their coverage to undermine morale on the home front. Subsequently, in the pro-government Christian, social democratic and liberal newspapers and journals, reporting was dominated by emotionally-distant photos and soothing articles supplied by the information services. This reporting was less and less about actual military activities and more about social-cultural issues and the humanitarian activities in the colony. Retaining civilian support During the second military action (December 1948) and the subsequent guerrilla war in the first half of 1949, the (international) press was no longer granted access to operational areas. This was an effective means of curbing (international) attention for the Indonesian struggle for independence. The army and navy information services now dominated the production, selection and distribution of photographs and articles to the press. There were no longer any current images published. The military information services engaged their strategy to keep the grisly guerrilla war out of the media. Specifically, this meant keeping war operations out of the headlines and allowing absolutely no shocking photos of dead or badly injured Dutch soldiers or Indonesian fighters in the newspapers and magazines. These sorts of images were never shown in the Dutch media, and the Dutch population was carefully shielded from violent images. This is not surprising, as violent photos could stir up strong emotions against the war. So no (photo) reports and newspaper articles were published about setbacks on the battlefield (including the many casualties on both sides),

Fig 1: Malang, East Java, end July 1947. Operation Product. KNIL soldiers (Royal Dutch-Indies Army) standing by captured, wounded and deceased Indonesian soldiers. Unpublished photo. Army photographer unknown.

the sometimes violent experiences of the Dutch conscripts and volunteers, and the hardships suffered by the local population during the intensive guerrilla war. The chaotic warzones and the reality of the fighting remained largely invisible. By omitting relevant (visual) information they were trying hard to keep morale on the home front high, to please public opinion and to minimise any anti-war sentiment among the Dutch people. The media was used to retain the support of the civilian population in the implementation of the government policy and, effectively, to use propaganda against the enemy, usually referred to as ‘roving gangs’. Letters from the front The information authorities and the compliant media emphasised reassuring images of the Indies archipelago. But the humanitarian mission, as it was portrayed in the propaganda, was not what the ordinary soldiers experienced, especially on Central and East Java, which were consistently under attack by Indonesian insurgents. And although the military information services were successful in keeping certain reports and images out of the media, they had no control over the letters from soldiers published in Het Parool, De Waarheid, Vrij Nederland and De Groene Amsterdammer, which revealed the drama that was taking place in the tropical archipelago. The letters and eyewitness accounts by soldiers reported extreme engagements with guerrilla fighters, but also the civilian population. While these allegations of violent excesses led to widespread public outrage at the time, in the absence of any visual proof of bombed kampongs and dead civilians and combatants, these acts of war remained hidden. Moreover, such reports were often denied, belittled or ignored by the government and the army leadership in Batavia. In reality, the colony found itself in a precarious position in the Spring of 1949. The (photo) coverage of the Dutch dailies and illustrated journals was, for the most part, a version of events propagated by the military information services and provided little independent and/or new (visual) information. This fit neatly with the desired image of the military top brass (General Spoor, spy chief Colonel Somer, the press chief Lieutenant-Colonel Koenders) and political elite (Catholic government leaders and HVK Beel in Batavia) about the military actions in the former Netherlands East Indies. The fight for public opinion was just as important as the actual battle being waged in the archipelago.

The Newsletter | No.68 | Summer 2014

The Study | 9

The military versus the media in the Netherlands East Indies 1945-1949 Fig 2: Malang, East Java, end July 1947.

2

Operation Product. Indonesian man, killed in battle. Unpublished photo. Army photographer unknown. Fig 3: Batavia, West Java, 10 March 1948. DLC information officer at work. Army photographer, ensign H.J. van Krieken Fig 4: West Java, July 1947. Operation Product. Young Indonesian men held at gunpoint. Unpublished photo. Army photographer/ camera man, lieutenant Wim Heldoorn

3

4

5 Foreign PR The DLC and MARVO (the army and navy information services) were virtually absolute rulers in the area of military information and propaganda. They censored all photo and film material in the name of operational security, public opinion and the need to uphold the morale of the population. No poignant or revealing war images were released. This strategy determined the image of the struggle in the former Netherlands East Indies. The censored material was archived and was only available to the military authorities. Initially, the DLC and MARVO maintained the impression that the colonial conflict was manageable and even winnable. This was a misrepresentation. Later, as the conflict progressed, Indonesian resistance increased, the violence escalated, and the lists of the dead became longer, the Dutch lost all chance for victory. By the end of 1948, during the second military action, the decisive DLC and smaller MARVO no longer even made any sophisticated use of the media. They blocked access for the (international) press to operational areas on Java and Sumatra; they postponed the forwarding of reports and images, by their own (photo) correspondents about the military actions, to the press. The cause of this suspension can be explained by interference from the United Nations, the US and Great Britain in the escalating military conflict. Foreign observers, correspondents and intelligence services meticulously followed the coverage in the Dutch (Indies) daily and weekly papers. Until that point, the Netherlands had been particularly inward looking with regards to information and (international) press awareness. Only after this military action did the information services see the light, after it became clear that the

Fig 5: Pesing, near Batavia, West Java, 15 April 1946. Indonesian prisoners of war, some in military uniform, work under Dutch military supervision. Context unknown – they could perhaps be digging their own graves, or the graves of their fallen comrades. Unpublished photo. Army photographer unknown. All images from the DLC Collection (Dienst Legercontacten), housed in the National Archives in The Hague.

Dutch government was receiving no support and international criticism was growing. The US even threatened to withdraw the promised Marshall aid for the reconstruction of the wardamaged Netherlands. Confronted with international isolation, The Hague and Batavia decided on a new media approach as well as spin-doctoring the effects of the conflict. The information services made common cause with an unexpected ally: the American media. In particular, Herman Friedericy of the NIB was active in the promoting of the Dutch standpoint in the USA. He advised the Dutch government to hire the American PR- bureau Swanson & Co to fight the negative image. The turning point was the goodwill press trip to the archipelago for a group of prominent American journalists in the Summer of 1949. During the fact-finding mission, these journalists became increasingly convinced that Sukarno was not the right leader to stop the rise of Communism in Southeast Asia. This was despite the fact that the nationalist Sukarno had executed a group of high-profile Communist leaders. Dutch spokesmen labelled the actual elimination of these top PKI figures as counter-propaganda designed to achieve favourable media attention in the US. The coverage of the travelling American press was greatly swayed by the growing Cold War atmosphere in Asia. They had no trust in the Republic of Indonesia and saw the continuing Dutch influence as a safeguard against the encroaching Communism. In short, they chose for a pro-Dutch position. However, the Dutch PR coup was destroyed in one fell swoop when the KLM airplane Franeker, carrying the group of prominent American journalists, crashed on the journey home. Another American PR consultant, John Boettiger, was hired to start a new media offensive and press campaign in the US. But it was too little, too late. Speaking out In summary, the professional information services more or less set the agenda and the news in the Netherlands with respect to the struggle in the Netherlands East Indies. In particular, they zoomed in on the information that supported their views; the rest was ignored. ‘White noise’ and ‘correct’ details predominated. They had a tendency to neutralise and justify the colonial conflict, and were very good at disguising the war as a humanitarian action. They engaged in muddied language and transparent propaganda. Today this is called perception management or strategic communication. In fact, they were

juggling information about war operations; independent (photo) journalism was limited by a cordon of (army) press officers. The Dutch-Indies government in Batavia stayed in close contact with the expensive American PR bureau Swanson & Co, but also with the overzealous information officers under the leadership of Herman Friedericy, of the Netherlands Information Bureau (NIB) in New York, in order to portray the Dutch presence in the colony in a favourable international light via the press, newspapers, radio and films. And, when necessary, the secret services, such as NEFIS/CMI, were employed. Power always has the tendency to interfere with journalism. At that time, the military press officers and spokesmen never spoke out against their superiors, and the often uncritical Dutch correspondents never went against their editors. Exceptions included the left-wing journalists Frans Goedhart and Jacques de Kadt from Het Parool and the astute NRC journalist Chris Scheffer, who was summarily dismissed because he dared to stick his neck out. Because journalistic reports and photos were censored and the majority of reporters censored themselves, the full reality of the war never penetrated the wider Dutch public. It is also striking that the Dutch media – with the exception of Het Parool, De Waarheid, Vrij Nederland and De Groene Amsterdammer – published harmonious copy (the tone was primarily reassuring) and neutral, meaningless photos taken by military information services. Dutch citizens were not well informed. Indeed, there was little provision for transparent information and only biased images about the struggle in the Netherlands East Indies. Louis Zweers was a former lecturer at the Department of History, Culture and Communication of the Erasmus University Rotterdam. He recently obtained his PhD and now works as an independent scholar and author. His thesis has been published: De gecensureerde oorlog. Militairen versus media in Nederlands-Indië 1945-1949, Uitgeversmaatschappij Walburg Pers, ISBN 9789057309397. (louis.zweers@ziggo.nl) Reference 1 This article is a translation of (an edited version of) the summary from Louis Zweers’ 2013 PhD dissertation: “Doodzwijgen leek de beste oplossing. Militairen versus media, Nederlands-Indië, 1945-1949” [‘Silence is the best solution’. The military versus the media in the Netherlands East Indies 1945-1949]

The Newsletter | No.68 | Summer 2014

10 | The Study

The challenges to female representation in Asian democracies Political life in Asian countries is often characterized as a man’s world, especially compared to its Western counterparts. Yet we have also seen increasing electoral opportunities for women in the region. Since 2000 alone, women have been elected prime minister in Bangladesh (Khaleda Zia in 2001; Sheikh Hasina in 2008) and Thailand (Yingluck Shinatwatra in 2011), and elected president in the Philippines and Indonesia (Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and Megawati Sukarnoputri both in 2001) as well as South Korea (Park Geun Hye in 2012).1 Furthermore, major parties, including the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) of Taiwan, have nominated a female presidential candidate (Tsai Ing-Wen in 2012).2 Timothy S. Rich and Elizabeth Gribbins

CURRENTLY THERE ARE seven female presidents and eight female prime ministers worldwide, six from Europe and three from Asia. Furthermore of the forty-one women elected to these offices since World War II, eleven were in Asian countries. More importantly, these women represent the broader political spectrum of the region and have not been limited solely to liberal-progressive parties. The election of South Korea’s Park Geun Hye, for example, almost immediately drew comparisons to conservative female leaders from Europe, namely Margaret Thatcher and Angela Merkel. Considering that women comprise half the world’s population, the factors that promote or discourage female leadership in politics require greater attention. This analysis adds to this research by connecting evidence from Asia to broader global trends. Executive structure Evidence from Asia provides several challenges to broader claims about female representation. Arguments suggesting that certain cultural contexts restrict opportunities for women have some merit. For example, the Middle East sees the fewest elected or appointed positions for women in politics, with Northern Europe seeing the most. Yet, this should not be conflated with a homogenous influence of Muslim culture, as predominantly Muslim countries, starting with Pakistan’s Benazir Bhutto in 1988 and followed by Indonesia and Bangladesh, have elected female leaders. Women have also found electoral success in most former communist regimes, where opportunities within the old regime partially translated into experience valuable in later democratic elections. Yet these cultural or historical experiences alone fail to explain patterns in Asia. Instead of rehashing arguments largely based on vaguely defined cultural distinctions or historical conditions, we present here additional factors that influence female representation. Global evidence suggests several institutional factors that contribute to female success in electoral competition. In terms of elections to executive office, women have been more successful in parliamentary systems than presidential systems. In part this is due to the ways in which heads of government are elected. In a presidential system, candidates must appeal to a broad cross-section of the population, obtaining a plurality if not an outright majority of the vote. This presents a difficult hurdle for any candidate, but especially for women if large segments of the population view women as unfit for office. In contrast, parliamentary systems provide a potentially lower threshold as a candidate can either be elected to parliament through a constituency seat (e.g., United Kingdom) or a party list (e.g., Denmark) and if in the majority party or coalition, then be appointed as prime minister. However, the evidence from Asia shows little distinction by executive structure, suggesting additional factors. Male predecessors One striking characteristic among many of Asia’s most successful female candidates has been their familial connections to dominant male figures from previous elections or the democracy movement more broadly. Indira Gandhi, India’s first female prime minister, arguably benefited from being the only child of Jawaharlal Nehru. Srimavo Bandaranaike of Sri Lanka, the first female head of

government in the 20th century, was the widow of a previous prime minister. Both female presidents from the Philippines (Corazon Aquino and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo) as well as Indonesia (Megawati Sukarnoputri) were related to former heads of government or major opposition leaders. Park Geun Hye of South Korea remains intrinsically tied to the country’s former dictator, her father Park Chung Hee, effectively playing the role of First Lady after North Korean spies assassinated her mother. International coverage of her campaign echoed this connection,3 with Park supporters opting to positively spin references to her ‘strongman’ father. The role of familial connections in Asia contrasts patterns seen elsewhere, with only three clear examples of a similar connection in female presidents: current president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner (Argentina), and former presidents Janet Jagan (Guyana) and Mireya Moscoso (Panama). The consistency with which, on the national stage, successful female politicians spring from strong political roots of course begs the question whether these candidates would have had similar success without the name recognition. Such name recognition provides at the very least an initial advantage to those otherwise with limited political experience, both in attracting media attention and in assisting in fundraising. Similarly, one must question whether supporters identify a distinct policy from these female leaders or simply associate them with the policies of their male predecessors. For example, despite claims to the contrary, Yingluck Shinawatra of Thailand remains framed by supporters, and opponents alike, as a proxy to her brother Thaksin Shinawatra, ousted in a coup in 2006. Thailand’s snap elections in February of 2014 were in part a result of a proposed amnesty bill that opponents claimed would lead to Thaksin’s return to the country. Similarly, Park Geun Hye attempted in part to appeal to the nostalgia over her father’s transformation of the South Korean economy, the so-called ‘Miracle on the Han River’, while attempting to distinguish herself in terms of North Korean policy from her predecessor and intraparty rival Lee Myung Bak. Filling the quotas Even if opportunities to the highest office remain in part linked to pedigree, women are seeing greater opportunities in national legislatures. Admittedly, Asian democracies still lag behind their European counterparts: women fill nearly twenty-eight percent of seats in lower house legislators in European democracies labeled ‘free’ by Freedom House, compared to fourteen percent in Asia.4 However, even Japan, where female representation in the House of Representatives rarely broke three percent, has witnessed meager increases. Female candidates have also benefited from gender quotas in legislative nominations and seat allocation, although seats set aside for women often do not incentivize party nominations beyond these areas, effectively limiting the number of female candidates overall. In other cases, quotas create a cohort of experienced officials that have a greater chance of winning elections in the future. Similarly, while gender quotas are consistently employed for placement on the party list in South Korea’s National Assembly elections, nomination to district races remains rare, with similar patterns also seen in Taiwan. The underlying rationale arguably is that parties remain concerned about whether female candidates can garner a plurality of the vote in district competition.

From left to right: Sheikh Hasina, Park Geun Hye, Tsai Ing-Wen, Yingluck Shinatwatra, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.

However, part of this concern is predicated on the lack of female candidates with political experience. Simply put, if women are not afforded opportunities to gain campaign and office experience at lower level offices (e.g., city councils), they are unlikely to attempt higher office, much less get a major party’s nomination. Lower level office Democracies in Asia face similar demands for greater female representation as seen elsewhere. As these countries gradually expand roles for women in lower level offices, we should expect similar increases in the number of women unrelated to previous leadership that receive nominations and succeed in legislative and executive offices. The pattern of women in Asia with familial ties breaking the electoral glass ceiling, if nothing else, provides role models for the next generation. Whether this familial pattern is a temporary legacy of the third wave of democratization, or a more enduring pattern, is unclear. One way in which Asian countries could take the lead in female representation is through the establishment of term limits for legislative offices and lower level positions, as existing evidence suggests term limits benefit female candidates.5 Due to incumbent advantages and a declining number of competitive districts, few district races afford women a realistic opportunity to gain seats. Proportional representation systems also potentially create a similar problem in that only a select few women, whether due to quotas or otherwise, are re-nominated. Regardless, until parties across the political spectrum actively recruit women for lower level offices as a means of gaining experience and name recognition, cracks in Asia’s glass ceiling will remain limited compared to its European counterparts. Timothy S. Rich is an assistant professor of political science at Western Kentucky University. (timothy.rich@wku.edu) Elizabeth Gribbins is an honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University. (elizabeth.gribbins994@topper.wku.edu) References 1 Other examples of women in national roles during this timeframe include Pratibha Patil (President of India 2007-2012), Roza Otunbayeva (Kyrgyzstan interim president 2010-2011), Chang Sang (acting prime minister of South Korea in July of 2012), and Han Myeong Sook (prime minister of South Korea 2006-2007). 2 While this analysis focuses on Asian democracies, even the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has seen a greater role for women, with Liu Yandong elected to the Politburo in 2012 and appointed vice premier in 2013. 3 Emily Rauhala. 2012. ‘The Dictator’s Daughter: Park Geun-Hye May Become South Korea’s Next President’, Time Magazine, December 17. (http://tinyurl.com/Park-Geun-hye) 4 Freedom House (www.freedomhouse.org); In contrast, European and Asian countries labeled ‘partially free’ differ marginally in female representation in lower houses (twenty-two and twenty-one percent respectively). Calculations do not include Taiwan. (www.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm) 5 Leslie A. Schwindt-Bayer. 2005. ‘The Incumbency Disadvantage and Women’s Election to Legislative Office’, Electoral Studies 24:227-244.

The Newsletter | No.68 | Summer 2014

The Study | 11

Like wildfire

The Writer